For years, software engineer Linus Torvalds—creator of the Linux kernel, the basis of the Linux operating systems—has been as well known for his combative attitude as for his tech.

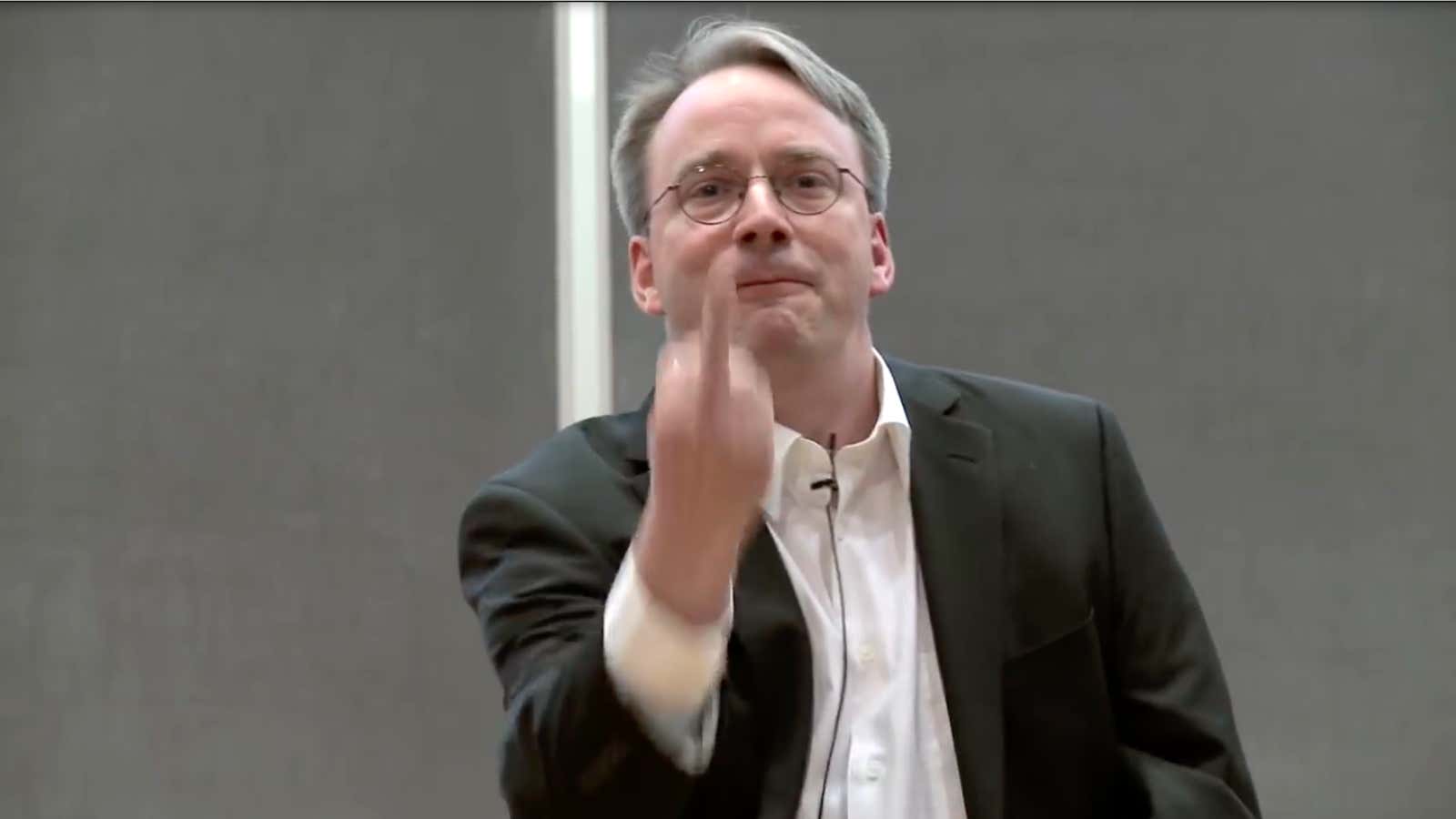

He lobbed vicious personal insults in public forums, at developers whose work he disdained. He once concluded a scathing assessment of a hardware manufacturing company at a Q&A by flipping off the camera recording the talk for the web.

“I’m not a nice person, and I don’t care about you,” he said at a 2015 conference, when asked about his behavior. “I care about the technology and the kernel—that’s what’s important to me.”

But his behavior did hurt the technology, as developers moved away from Linux to avoid Torvalds’s attacks and outbursts. After years of unapologetically defending his behavior, Torvalds—for reasons that aren’t yet entirely clear—says he wants to change.

“I want to apologize to the people that my personal behavior hurt and possibly drove away from kernel development entirely,” he wrote in a letter posted to a Linux forum. “I am going to take time off and get some assistance on how to understand people’s emotions and respond appropriately.”

It’s a worthwhile goal—but is it something an adult can be taught?

Most people learn empathy in childhood. Some don’t, for both neurological and personal reasons. People with autism and schizophrenia often struggle to identify other people’s emotions and respond appropriately, as do people with antisocial or narcissistic personalities.

The idea that ethics are something you’re born with—or not—frames respect or empathy as a thing that a person has, rather than something that is expressed through behavior. But evidence abounds that motivated adults can indeed learn to act in different ways.

Behavior training breaks down into four parts that remain consistent whether the student is learning a new workout move or a new skill at work, as behavioral science professor John Malouff of the University of New England explains in The Conversation.

First, an instructor describes the desired behavior. Then they model it for the student. The student practices it themselves, and the instructor gives feedback, in a sequence repeated as many times as necessary. A student of empathy, or of respectful workplace interactions, might watch a live or online demonstration of interactions in which the speakers display appropriate responses to one another.

And it works. In one small experiment published in 2009 in the journal Academic Medicine, a group of teaching physicians who went through an 18-month compassion training course received consistently higher marks on bedside manner and patient interactions, compared to a control group that didn’t have the training.

“I honestly despise being subtle or ‘nice,'” Torvalds once wrote when challenged about his behavior. That doesn’t really matter. Respectful behavior is less about feelings than about actions, and actions can improve with training and practice. You don’t have to like being decent to other people; you just have to do it.

One important thing to note: When Torvalds gave that company his middle finger and a public cursing, the room erupted in laughter and cheers. Bad behavior is much harder to change when you’re surrounded by people who encourage it.